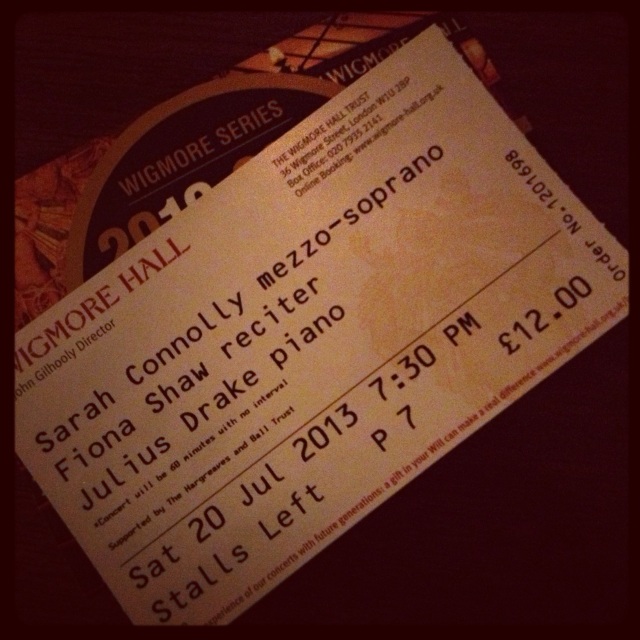

On Saturday, I found myself in a train to London again, after an impromptu decision to go and see Sarah Connolly and Fiona Shaw perform texts by Virginia Woolf at the Wigmore Hall. It turned out to be a very interesting evening in more ways than one. Virginia Woolf is one of my favourite authors. Fiona Shaw is probably my favourite actress. I love Sarah Connolly. But the most interesting, inspiring people I met and saw were actually those in the audience – strangers passing me by, but leaving their mark nonetheless.

This isn’t really a review, but it would be shame not to say anything about the recital, especially about Fiona Shaw. Sarah Connolly is a strong, charismatic stage presence, but somehow, to me, her performance was left in the shadow – a vocally mesmerising, voluptuous shadow, reserved in its presence next to the exuberance with which Shaw carried herself, completely unself-conscious and without a trace of vanity, throwing her whole being into the text and letting it carry her. This performance alternated Dominick Argento’s songs to Virginia Woolf’s diary entries with excerpts from her novels, essays and diaries, scripted together by Dr Kate Kennedy of Girton College, The Other Place, and moving chronologically from the 1920s to 1941 – Woolf wrote her last diary entry the day before she, unable to overcome her depression, drowned in River Ouse. What the song cycle calls the last entry isn’t really – Woolf wrote about cooking haddock and sausage meat for dinner about three weeks before she died, but the actual last entry isn’t much less banal, describing the people she had met that day. It is a haunting insight into the soul of a genius, a famous quote, often cited as humorous and witty, when in reality it was everything but. Woolf was struggling to keep her hold of reality and of life, and accounting the ordinary is surely an expression of that. This performance gave those few lines she wrote bautiful poignancy – the two performers, moving on the stage seemingly ignorant of each others’ presence, finally came together, shared a spotlight, Connolly as the inner voice of Woolf, Shaw as Woolf herself – her pen moving long after the music had stopped, the audience holding its collective breath until those final words had been written down and the book closed one last time. It was all about Virginia Woolf and her voice, the performers on the stage fading behind her.

Still – the writer in me couldn’t help but to be inspired by their personalities. Shaw and Connolly share the same basic physicality. They are both tall and plainly, regally beautiful rather than conventionally pretty. One glamorous and polished on stage, the other carelessly bohemian. I see a story here – of two sisters perhaps. One beautiful and fashionable, the other fiercely intellectual, each eternally suspicious of the other, eternally bound together by loyalty and love and mutual resentment. Or of Bloomsbury lesbians, Woolf’s contemporary; a bored married woman and her mistress, an unconventional, snobbish intellectual, let down by her lover’s inability, lack of courage, to choose one world in which to belong. It is a story that will never be written, but for a moment I could see it take shape.

Dr Kate Kennedy had chosen music as her theme for the recitations to rhythm the songs – Woolf spent much of her time in concerts, sitting at the back of Wigmore Hall listening to chamber music, her mind wandering as the music played, lifted by the notes. She found peace and inspiration both in music and in the ritual of going to a concert, sitting in the darkness of the concert hall where she could let her mind whirl free. Woolf sometimes regretted that she was not an educated scholar of music, but she wouldn’t let her lack of proficiency to get on the way of simple enjoyment and desire to learn. She wrote about music, expressed her opinion, sometime boldly, and wasn’t afraid of doing so.

Seated next to me were a group of eminent Woolf scholars from Cambridge – the sort of academics one thinks of when imagining how Oxford or Cambridge must be like, like characters out of the pages of Gaudy Night. Clever. Terrifying. Straightforward. Completely inspirational in the way they seem to radiate intellectual strenght and discipline and sheer, wilfull ignorance of social trivialities. I have no delusions of my own academic capabilities, and I never had a particular yearning to become part of that world, not even when I spent my time shuffling between the more obscure branches of the Oxford University’s library services as an undergraduate. But some years down the line, I do occasionally miss it – most often when I’m cycling past some particularly fine library, and catch through the windows a glimpse of all the old books on the shelves, and of the students and scholars poring over them. It’s a secluded world, a privileged one, and yet one where so much of the real work of the world is done. I pass the Radcliffe Science Library and all the adjoining science departments daily, and often think that inside these walls someone is finding a cure for cancer or an endlessly renewable source of energy at that very moment. Somewhere someone is reading a document – long hidden under a filing cabinet that someone just moved, first time in hundred years – that will change our understanding of the history, and with it, of where we are now.

After the recital I pulled my ancient copy of Woolf’s A room of one’s own out of my bookshelf and started rereading it, first time after many years; partly to enjoy Woolf’s distinct, ornate writing style, and partly because the basic sentiment of the book has always made sense to me. To write, she wrote, a woman needs a room and money of her own. In short, she needs resources that will free her time and her mind to the kind of idleness that is necessary for creative process. I work 50 hours a week, tied to my desk, and so often find that the moment of inspiration passes because my mind isn’t quiet enough to mull over, to process the ideas I have. There is little time or energy for research, reading, toying with ideas so that they could grow into something tangible. I dream of such time I can sit down and read and write, fill out all the sketch books I have, learn something new – come the autumn, recharge my brain by attending online courses of Berkeley University, a longtime dream of mine. Photography has become my main creative outlet not least because of its spontaneity. While I do think and plan ahead projects and go out on purpose to shoot pictures, I can still make an image only of what I see on that very moment. The passing glimpse of sunlight or rain, of people coming together is the inspiration, there to be captured before it’s gone forever.